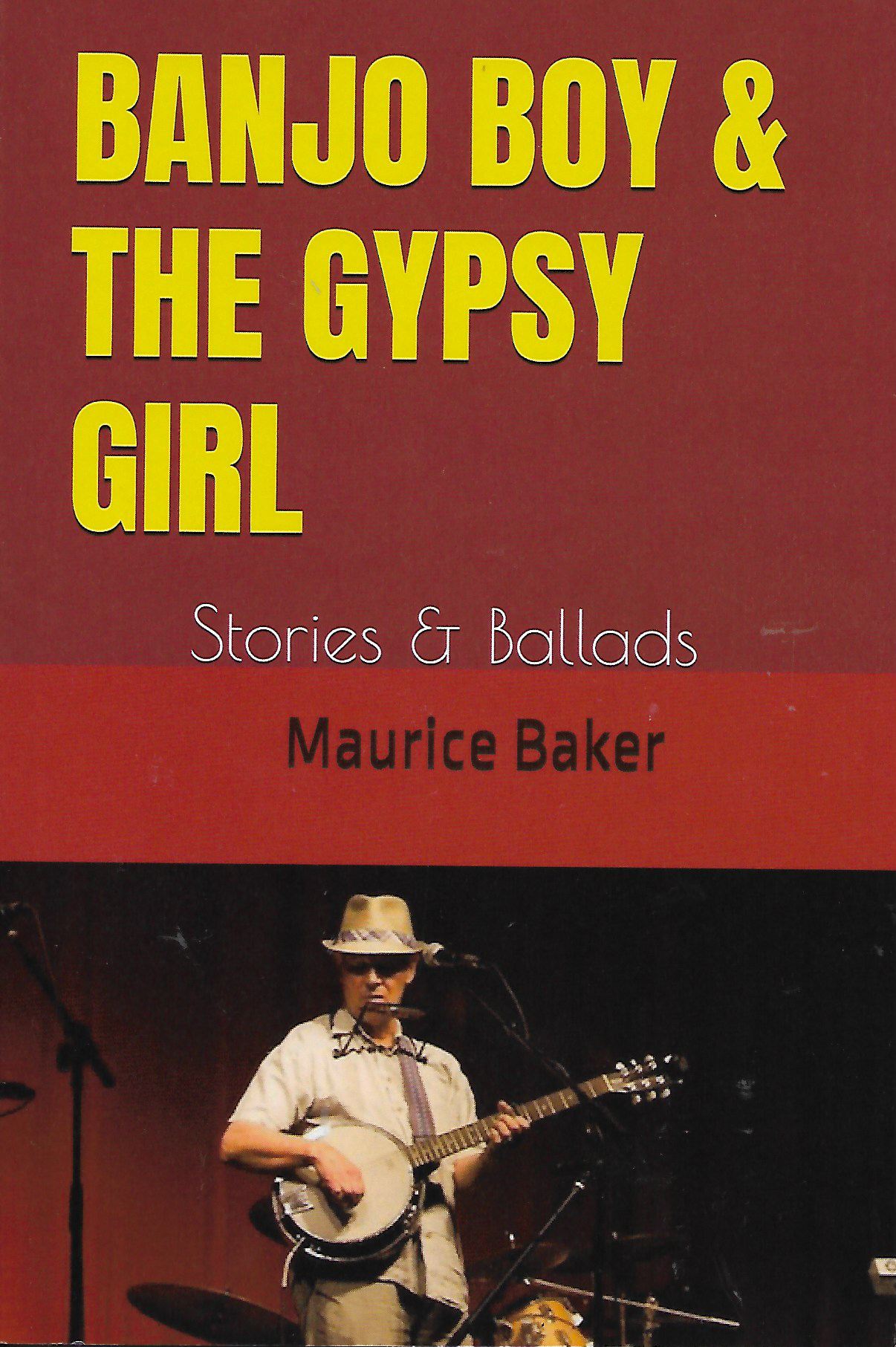

Banjo boy and the gypsy girl, you should’ve heard them play,

all along the Cote d’Azure from Monaco to Marseilles.

Sleeping on the beaches and drinking in the bars,

no hotel reservations when you’re dancing…

dancing beneath the stars.

Banjo boy and the gypsy girl, you should’ve heard them play.

Begging on the boulevards, the boutiques, and cafes.

Hiding from the gendarmes, running from the past,

working the Riviera like nothing, nothing… nothing good can last.

From here until forever, Marrakesh or Kathmandu.

Maybe catch that magic bus, another month or two.

Or sail the ancient islands beneath an endless sky,

Just like the old Egyptians, and never, never, never…

Never say die.

Banjo boy and the gypsy girl, you should’ve heard them play.

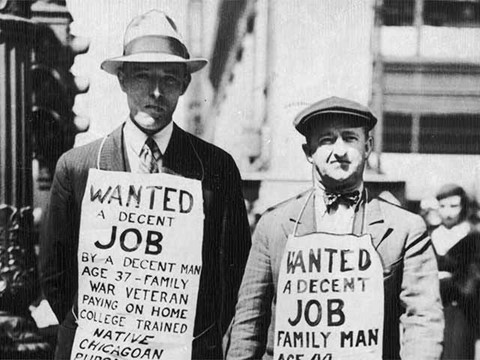

Back in the nineteen-sixties, I heard some old guy say.

Didn’t need no permit, no insurance, and no phone.

Did what the hell you wanted, free, free, free…

free as a bird to roam.

Banjo boy and the gypsy girl, you should’ve heard them play.

In and out of trouble, man those were the days.

Before the hitch-hike highway became a Trip Advisor trail,

And I traded in my banjo for a life… a life that could not fail.

This song – which I wrote about ten years ago and based on experiences hitching around Europe as a teenager – was, in turn, the inspiration for the following short story, Other songs, poems and tales included in the book are mainly on the topic of travelling.

NO WORRIES – short story

‘I wonder how they did it?’

‘Did what?’ asked Sue.

‘Get all the stone to build this place.’

‘There’s probably a quarry around here somewhere.’

‘Maybe, but they still had to cut it up and transport it – tons of the stuff. And that was hundreds of years ago with only basic tools and ox carts travelling on muddy tracks.’

‘Umm,’ she muttered, indicating her mind was on weightier matters, like the exorbitant entrance charge, the quality of afternoon tea and, most importantly, the state of the loos.

Of course, these things concerned me too, but I always tried to take the long view – like how the hell had the Swyzle family acquired Cedar Heights from the original owners, gentry since the Norman conquest? Maybe some courtier did the dirty on a rival and this was his reward? Or it was pay-off to a royal mistress? Whatever the case, at a time when land meant money, the Swyzles had done all right for themselves.

But for how much longer? What with death duties, swingeing taxes, and rising overheads, a family’s fortune could easily be eroded and even lost altogether.

Leaving Sue to explore the garden, I went to view the house and found an elderly woman sitting by the entrance.

‘Hello,’ I smiled. ‘Is it okay to come in?’

‘Of course. And feel free to ask anything.’

Peering around the gloomy interior I noted a number of framed photos, and one caught my eye – a family, posing before a large Art Deco building and labelled: Lord and Lady Swyzle with children, Gregory and Leticia, summer 1965.

‘You?’ I asked, indicating the teenage girl.

‘Yes. Our last trip together. Le Casino de Nice, on the Promenade des Anglais.’

‘And what’s that?’ I said. ‘Under your arm?’

An African drum. It belonged to Jamal – the young Tunisian beggar boy who took the photo.’

‘Really?’ I said. It seemed incongruous – an aristocratic English family and an African street urchin. Or maybe the lad was more than that? Trying to be discrete, I asked about the instrument.

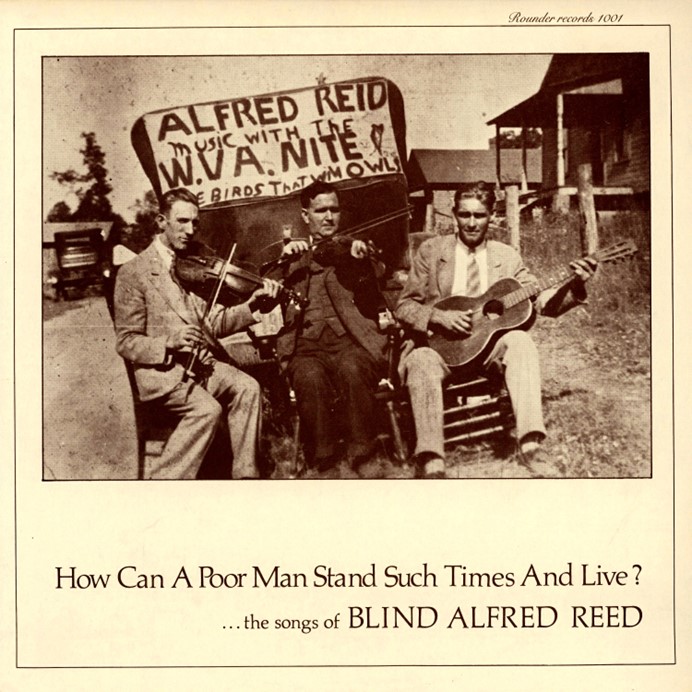

‘The djembe? He could almost make it sing,’ she informed me. ‘Worked with an Irish guy named Patrick. A great banjo player.’

‘He was a busker too then?’ I asked.

‘Oh yes. They were brilliant. Jigs and reels mostly, with a few pop tunes thrown in. And, of course, some amazingly hypnotic Berber numbers.’

‘So what happened?’

‘Well, I’d bought this long tie-die skirt in a flea market. I loved it, but mother felt otherwise. She was very strict about keeping up appearances. Treated me like a doll. I guess I’d just had enough. Sneaked out of our hotel, found Paddy and Jamal entertaining on the prom and joined in – dancing along to the music. Though later I taught myself tin whistle and also learned a few songs. The crowd loved us and soon began throwing their francs. I was hooked from day one.’

‘You mean there were other days?’ I asked.

‘Sure, my parents hardly missed me. Daddy spent most of his time at the baccarat tables and Mummy was either shopping or attending social soirees.’

‘What about this place?’ I wondered.

‘Oh, visiting the Riviera was their annual pilgrimage – never mind if Cedar Heights went to rack and ruin.’

‘But you kept on dancing?’ I asked.

‘Yup. All the way to Saint Tropes and beyond. Once Daddy realized I’d flown the coop he hired a car and chased after me. We had a blazing row but Patrick managed to calm him down and promised to take good care of me. Sure, we were sleeping on the beaches or in cheap hostels, but there was no funny business. So long as Paddy got his bottle of cognac each night he kept to his own bed.’

‘What about Jamal?’

‘After thieving the camera in Nice, he became obsessed with snapping people – especially celebrities.’

‘You mean actors? Stars of stage and screen?’

Oh yes. There were lots of wealthy people with yachts and villas. We often got invited to parties, and Jamal kept clicking away.’

‘So what happened at the end of the summer?’ I asked. ‘Did you go home?’

‘No, we carried on to Barcelona and then took a ferry across to Ibiza. Back then it was just a quiet little island – no big hotels or clubs and dirt cheap to live. A haven for artists, writers, and other dropouts. We stayed a month or two till the money ran out.’

‘And then what?’ I asked.

‘Well, we all went our separate ways, promising to meet up in Nice the following year. In the meantime, Paddy traveled to Berlin and became a session musician and I returned home and went to college, then London working for an oil company.’

‘And Jamal?’

‘Unbelievably, he was the most successful. Traveled to Paris and hawked his photos around the galleries. Kept himself alive drumming on the street. Dodging and diving. Mostly illegal, you know? Eventually he was offered a small exhibition but soon became the talk of the town, ending up a celebrated society photographer.’

‘So you never hit the road again?’

‘We followed each other’s careers from afar, but no, we never met up again.’

‘And there’s no record of you all together?’

‘Nothing. Yet that summer busking changed everything for us.’

‘But this place – Cedar Heights – it survived too?’

‘Just about, though now it’s owned by a charitable trust. Not long after returning from Nice, Daddy suffered a stroke and my brother took over running the place. He instigated many improvements, such as the flower festival today.’

‘So you live here now?’ I asked.

‘Well, it suits me. I have a small apartment and a few belongings. More importantly, I have my memories – the days when I danced for my supper with no phone, internet, credit card, TV, or money. And, especially, no worries.’

‘And the stone?’ asked Sue. ‘Did you discover anything?’

‘Nah,’ I said. ‘Probably like you said – brought from a local quarry. Manhandled by hundreds of peasants. Life was cheap and dirty back then.’